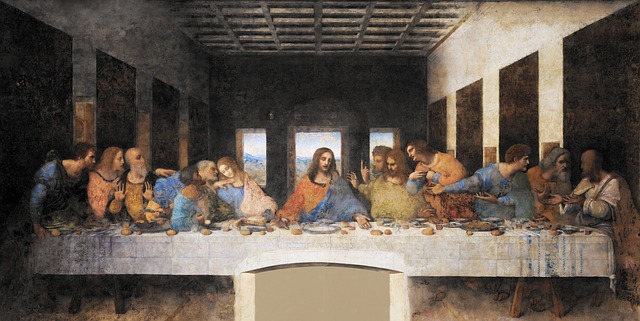

The Last Supper

“The Last Supper” by Leonardo da Vinci, painted between 1494 and 1498, holds immense cultural and religious significance. Created during the Italian Renaissance, it is a masterpiece that went above and beyond artistic boundaries. The painting had deteriorated over the years and in 1978 it was taken for restoration which took 21 years! Culturally, it symbolises the height of Renaissance innovation, showcasing da Vinci’s mastery in capturing human emotion. If you would like to see this fully restored painting you will have to travel to Milan in Italy.

Religiously, “The Last Supper” illustrates the moment Jesus reveals that one of his disciples will betray him, a pivotal event in Christian theory. The painting captures the emotional reactions of the disciples, and its portrayal of the Eucharist has become an enduring symbol in Christian art. The work has shaped perceptions of this sacred moment, influencing countless depictions of the Last Supper in subsequent centuries. The intersection of artistic brilliance and religious narrative in da Vinci’s masterpiece ensures its lasting impact on both cultural and spiritual realms.

The Wheel Of Life

The Wheel of Life (also known as Bhavachakra) painting in Buddhism is found in regions with a Tibetan Buddhist influence, such as Tibet, Bhutan, parts of Nepal, and northern India. Culturally, it serves as a visual narrative, depicting the cyclic nature of existence and the consequences of one’s actions! The intricate symbolism within the wheel, portraying various realms of existence and the perpetual cycle of birth, life, death, and rebirth, embodies the core teachings of Buddhism.

Religiously, the Wheel of Life captures the fundamental Buddhist principles of karma, impermanence, and the path to enlightenment. Illustrated are four layers. The centre of the wheel represents 3 poisons – aversion, atatchment and ignorance. Next is the second layer, showing the significance of karma. The third layer represents six realms, which is the magical cycle of existence. The fourth layer represents twelve links of dependent origination. In the representation the one holding the wheel is known as Yama who is also known as the lord of the underworld. Yama protects Buddhist people and Buddhism. Yama’s finger on the wheel of life is an indication that ‘Liberation is possible’.

Chagall Windows

The Chagall Windows, located in the Hadassah Medical Center Synagogue in Jerusalem, are culturally and religiously significant in Judaism. Created by the renowned artist Marc Chagall, these twelve stained glass windows vividly depict the twelve sons of Jacob, combining traditional Jewish artwork with Chagall’s unique artistic style. Chagall made stained glass windows for five other countries including Israel, France, Switzerland and Germany. Culturally, Chagall’s work has often been praised for its ability to bridge the gap between modern art and Jewish tradition, bringing a contemporary aesthetic to ancient stories.

Religiously, the Chagall Windows contribute to the synagogue’s sacred space, filling it with a vibrant visual narrative of the ancestral lineage of the twelve tribes of Israel. Each window tells a story from the Book of Genesis, visually connecting worshippers to their religious heritage. The windows serve as a testament to the intersection of art and spirituality, enriching the cultural and religious experience for those who gather in the synagogue, creating an environment where the sacred narratives of Judaism are not just heard but visually celebrated.

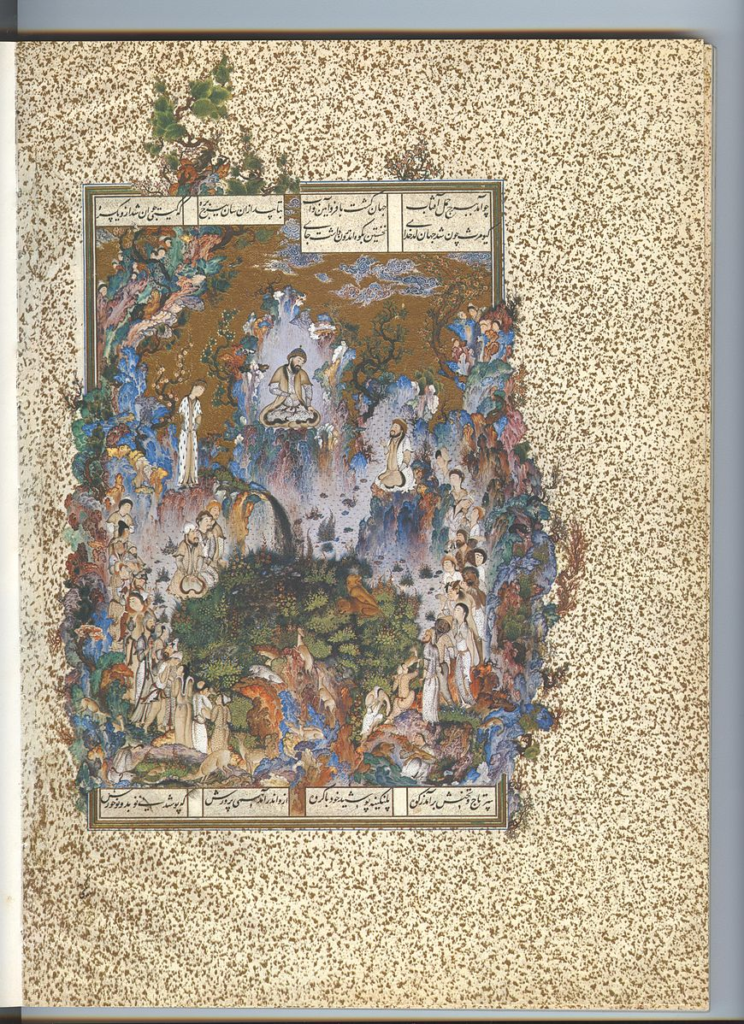

Court of Gayumars

The “Court of Gayumars” holds profound cultural and religious significance in the context of Islamic art. Culturally, this masterpiece, found within the pages of the Shahnameh, reflects the rich heritage of Persian civilization during the Islamic Golden Age. The intricate illumination work and vibrant colors used in depicting the mythical court of Gayumars showcase the levels of art of the time, combining Persian cultural elements with the broader Islamic artistic tradition. The Shahnameh, written by Ferdowsi, not only preserved pre-Islamic Persian legends but also became a tribute to the bond of Persian and Islamic cultural expressions.

Religiously, the Court of Gayumars within the Shahnameh echoes broader Islamic values of justice, order, and morality. While the Shahnameh primarily draws from pre-Islamic Persian myths and legends, its creation and preservation within the Islamic world reflect the liunk between cultural identities. The portrayal of Gayumars, often considered the first human and a figure of great wisdom, can be interpreted within Islamic contexts as well, aligning with themes of divine wisdom and moral guidance present in various Islamic traditions. Therefore, the Court of Gayumars stands as both a cultural treasure and a testament to the diverse influences shaping Islamic art and literature.

Matsya Avatar

The painting depicting the Matsya Avatar holds profound cultural and religious significance within Hinduism. Culturally, it is a vibrant expression of artistic traditions that have evolved over millennia in India. The detailed portrayal of Lord Vishnu as a colossal fish, often set against cosmic backgrounds, reflects the aesthetic brilliance of Hindu art. Lord Vishnu is also known as the sustainer of the universe and the principal deity in Indian mythology!

Religiously, the Matsya Avatar painting captures a pivotal episode in Hindu origins. According to Hindu mythology, as the world faced a catastrophic deluge, Lord Vishnu took the form of a fish to rescue the sage Manu and the sacred Vedas. The image symbolises divine intervention, protection, and the cyclical nature of creation, preservation, and dissolution in Hindu beliefs. The Matsya Avatar is not just a visual representation but a sacred narrative, illustrating the foundational principles of dharma in Hindu belief.

Guru Nanak with Bhai Mardana

The painting of Guru Nanak with Bhai Mardana by Sobha Singh is a vibrant representation of Sikh heritage and artistic expression. Sobha Singh, an esteemed Sikh artist, captures a serene moment in Sikh history, depicting Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism, playing the rabab, a musical instrument, while Bhai Mardana accompanies him. Guru Nanak and Mardana were brought up in the same village. The Miharban Janam Sakhi says that Mardana was ten years elder to Guru Nanak and was his companion since his childhood days!

Religiously, the painting portrays a pivotal aspect of Sikh philosophy and the life of Guru Nanak. The scene reflects Guru Nanak’s emphasis on the equality of all individuals and the unity of spiritual and worldly pursuits. The symbolic relationship between Guru Nanak and Bhai Mardana, where the spiritual leader engages in devotional music, signifies the integration of music and spirituality in Sikh worship. Bhai Mardana, a Muslim by birth, epitomises the universal and inclusive nature of Guru Nanak’s teachings. Guru Nanak invented Langar, which translates to communal kitchen, every Sikh temple in the world has a kitchen which distributes free meal all day every day, regardless of faith gender age or status. He was also one of the most travelled people in history, travelling as far as the middle east, europe and east Asia, only accompanied by Bhai Mardana for 20 years of travelling, on foot!